From a celebrated author, the thrilling sequel to Parable of the Sower.

"In the ongoing contest over which dystopian classic is most applicable to our time, Octavia Butler's 'Parable' books may be unmatched."—The New Yorker

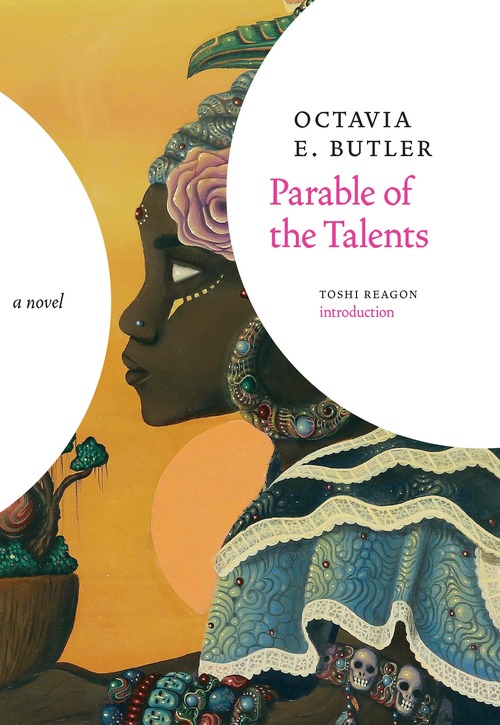

New Introduction by Toshi Reagon

Parable of the Talents celebrates the Butlerian themes of alienation and transcendence, violence and spirituality, slavery and freedom, separation and community, to astonishing effect, in the shockingly familiar, broken world of 2032. Long awaited, Parable of the Talents is the continuation of the travails of Lauren Olamina, the heroine of 1994's Nebula-Prize finalist, bestselling Parable of the Sower. It is told in the voice of Lauren Olamina's daughter—from whom she has been separated for most of the girl's life—with sections in the form of Lauren's journal. Against a background of a war-torn continent, and with a far-right religious crusader in the office of the U.S. presidency, this is a book about a society whose very fabric has been torn asunder, and where the basic physical and emotional needs of people seem almost impossible to meet.

As Butler herself explained, "Parable of the Sower was a book about problems. I originally intended that Parable of the Talents be a book about solutions. I don't have the solutions, so what I've done here is looked at the solutions that people tend to reach for when they're feeling troubled and confused."

And yet, human life, oddly, thrives in this unforgettable novel. And the young Lauren of Parable of the Sower here blossoms into the full strength of her womanhood, complex and entirely credible.

Don't miss the first book in the Parable duology, Parable of the Sower

Excerpt: Introduction to “Parable of the Talents” by Octavia Butler